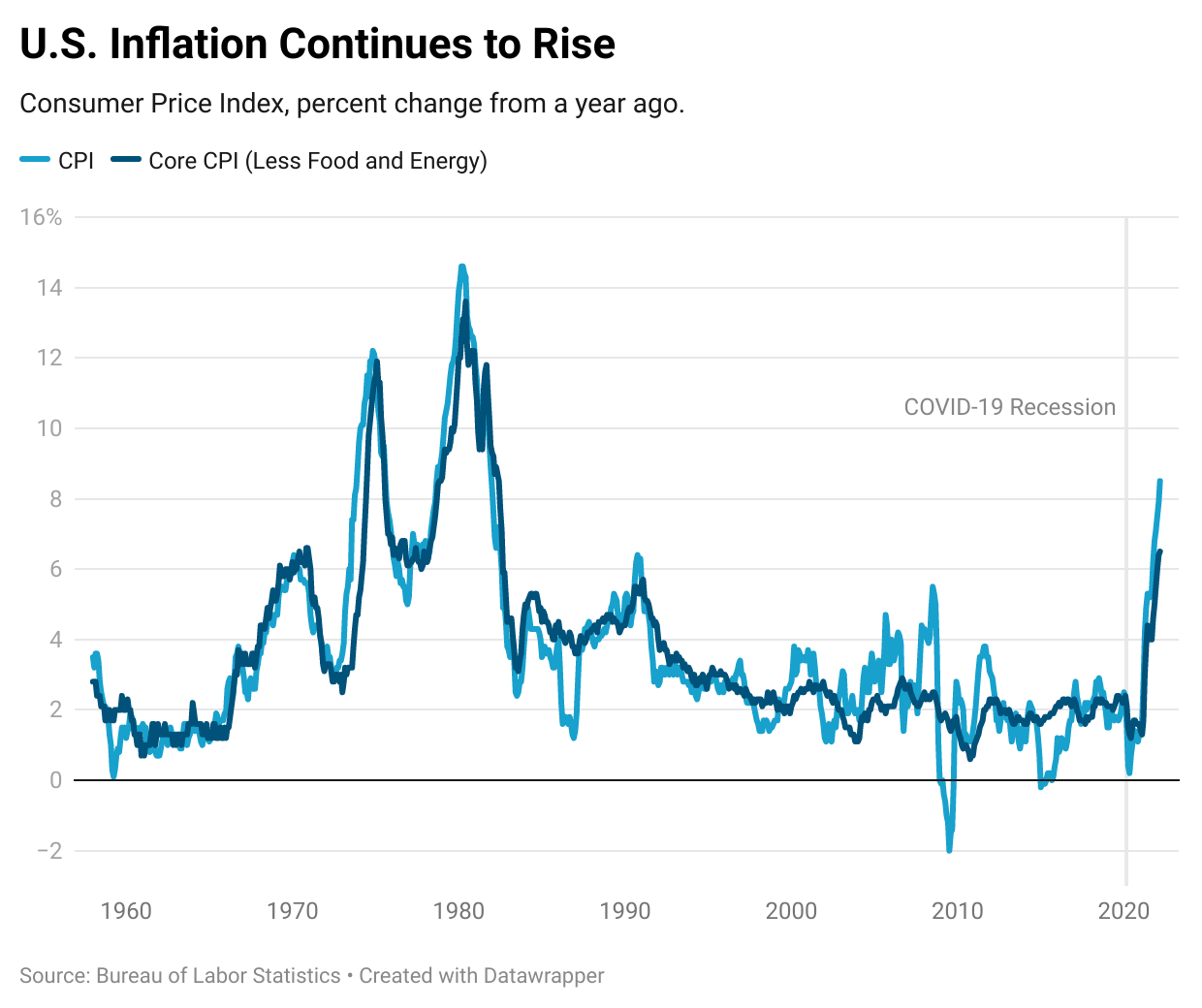

The theme driving markets throughout 2021 and coming into 2022 has been inflation, with consumer prices coming in consistently higher every month since March of 2021. The latest consumer price report showed inflation rising 8.5% in March, unsettling markets as investors feared that spiraling inflation would force the Fed to pursue tightening monetary policies quicker than anticipated. Once thought of as transitory and casually dismissed by investors and policymakers, we are now seeing a shift in attitude towards inflation as consumers, for the first time in 40 years, begin to bear the brunt of rising prices.

All this is happening during a time of: 1) rising asset prices (stocks, bonds real estate) 2) rising wages 3) and, not so long ago, the federal government putting money into the pockets of the American people. Although not everyone has benefited equally, Americans overall have the seen their collective net worth rise dramatically since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the rise in incomes and net worth may give some people the impression of becoming richer, they have not factored in the loss of buying power their wealth has experienced with today’s inflation.

What's Driving Inflation

While the COVID-19 recession was unprecedented in both size and speed, the U.S. economy has largely recovered, managing to register the shortest recession in U.S. history of just two months. However, the speed of the recovery was not without its consequences as while economic growth recovered, it came back accompanied with higher inflation. The drivers of today's bout of inflation and the length it will persist continue to be hotly debated, but I think a few notable factors should be mentioned.

Supply Chain Disruptions

When the pandemic first hit U.S. shores, it caused two anomalies: 1) nationwide social distancing measures and fears of contracting the virus caused consumer spending to collapse, leading to soaring inventory levels as businesses were stuck with billions of dollars in unsold goods (as can be seen by the spike in the inventory-to-sales ratio at the beginning of 2020), and forcing businesses to liquidate excess inventory and cut production in anticipation of further declining consumer demand 2) what was left of consumer spending - supported by stimulus checks provided by the government - was redirected towards goods rather than services as consumers were unable to spend on restaurants and experiences.

To put it simply, production was severely cut during a time demand for goods surged.

The supply-demand imbalance is especially apparent in durable goods as people purchased new electronics for entertainment and the transition to a work-from-home setting, exercise equipment to replace their gym memberships, cars to avoid public transportation and materials to renovate their homes. But forget about purchasing a car, it looks like even garage doors are in short supply.

With the country coming out of the pandemic, consumer demand continues to accelerate while supply shortages are further exacerbated by complex supply chains, rising commodity prices and shipping congestions. Now the argument is that these supply chain issues will slowly resolve itself and inflation will come down as these bottlenecks are dealt with. But fixing the global supply chain will involve fixing many moving parts, none of them easy to resolve.

For more insight into the complex nature of supply chains and ocean shipping, here are two videos by Wendover Productions I found insightful.

Extremely Tight Labor Market

After seeing unemployment skyrocket to levels reminiscent of the Great Depression during the onset of the pandemic, we are now experiencing the inflationary effects of an extremely tight labor market. The latest unemployment figure shows the unemployment rate falling to 3.8%, practically back to where it was before the pandemic hit U.S. shores and far from the peak of 14.7%. We are now seeing many more job openings than unemployed people looking for work.

Further exacerbating the labor shortage, many who left the workforce during the initial outbreak are not likely to return, as many have already passed their prime working age of 65 and are likely permanently retired.

Those that remain in the workforce are now experiencing new leverage they have with workers unsatisfied with their current employment quitting their jobs in search of better pay and career prospects. Further, resignation rates don't show any signs of slowing any time soon, with 4.4 million people quitting their jobs (2.9% of Americans) in February on top of the 47 million who quit in 2021, a trend many have deemed the Great Resignation.

Widespread labor shortages has forced employers to raise wages in attempt to attract and retain workers as demand continues to far exceed supply. With labor shortages already hitting industries like leisure and hospitality, trade and transportation, health services, and manufacturing hardest, we are likely to see the ongoing labor shortage worsen as consumer spending flows back into labor-intensive service industries.

As the economy continues to loosen COVID restrictions and more job openings continue to pop up without the necessary workers to fill them, employers will be forced to offer higher wages to entice workers, fueling a self-reinforcing inflationary spiral.

The Russian-Ukraine War and Surging Commodity Prices

Even before geopolitical tensions between Russia and Ukraine escalated into a full-scale war, the world was already grappling with energy shortages. In the early months of the COVID-19 crisis, global energy consumption plummeted, driving energy prices to their lowest levels in decades. But since then, energy demand has rebounded strongly without the necessary supply to meet it. While the surging demand is mostly the result of an exceptionally swift global economic recovery, supply constraints are due to a combination of factors.

Investments in oil production declined significantly over the past decade, as the collapse in oil prices in 2014 and 2020 made it unprofitable for shale companies to drill additional oil wells.

Before the pandemic hit, major nations such as the EU, China and the U.S. (albeit embarrassingly behind), were cutting coal and fossil fuel use in an attempt to bring down carbon emissions and speed up the transition to renewable energy; however, existing sources of clean energy were insufficient in meeting the demand that came with the global economic recovery.

Unfavorable weather resulting in a severe Northern Hemisphere winter and low wind output.

Metals tell a similar story with inventory of many base metals sitting at extremely low levels. Looking ahead, these shortages are not likely to be resolved any time soon because of the significant underinvestment in mining with capex spending falling by around 40% over the past decade. Moreover, increasing investments will only place further strain on the limited supply that is available now.

While Russia and Ukraine contribute little to the global economy in terms of their share of global GDP, both nations are major producers and exporters of many natural resources and agricultural products. In addition to being a leading exporter of oil and metals, Russia is also the largest exporter of nitrogen fertilizers in the world. Recent sanctions by Western nations following Russia's invasion of Ukraine have caused fertilizer prices have soared 30%, fueling fears of a global food shortage. Additionally, if that wasn't bad enough, it might be worrisome to hear that Russia and Ukraine make up one-third of the world's wheat production.

Given Russia's standing as a leading supplier of commodities, agricultural products, and oil and natural gas, we've seen some extreme reactions within commodity markets. And with markets clearly already concerned with high inflation, rising commodity prices are only adding fuel to the fire.

Inflation on Asset Returns

Inflation in the U.S. has been low (at times, even too low) for the last three decades. However, there are three standout periods when the U.S. grappled with high inflation, with it at the highest during the 1970s and spilling into the 1980s.

To assess how different asset classes performed during periods of high inflation, I compiled the annual returns on stocks (using the S&P 500 Index), bonds (using 10-Year Treasuries), real estate (using the Case-Shiller Index), gold and a few commodities, broke down the data by decade, paying particular attention to the 1970s and '80s.

The worst decade for stocks was the 2000s, largely thanks to the '08 financial crisis, followed by the 1970s when the U.S. experienced its worst bout of inflation. Bonds tell a similar story, performing poorly during the '70s. Real estate, while not spectacular, has shown to be resilient regardless of the macro-environment, keeping pace with inflation during the '70s. Gold and silver had their best decades in the 1970s, due to the U.S. dollar decoupling from the gold standard, and in the 2000s, as investors lost faith in the global financial system and looked to the precious metals as a safe haven amid the financial crisis.

Inflation and Bonds

To understand how inflation affects bonds, let's first establish that a bond is an investment that offers fixed periodic interest payments (measured as a bond's yield) and the eventual return of principal at maturity. Since interest payments are fixed, we can assume that investors would take expected inflation into account when looking at a bond and its yield. For example, if inflation was expected to be 3%, a rational investor would demand a yield higher than 3%. As a result, expected and unexpected inflation influence bond prices and yields in very different ways.

Expected inflation: Expected inflation is the inflation rate that investors anticipate in the future and take into account when purchasing a bond. Simply put, if investors anticipate higher inflation, they will demand a higher yield.

Unexpected inflation: Once a bond is purchased, investors are exposed to actual inflation. If actual inflation comes in higher than expected relative to the time of purchase, investors face a real loss on their bond as returns are eroded away by inflation. Purchasers of the bond may react by selling it, pushing prices down and yields up. On the other hand, if actual inflation is lower than expected, bond prices rise and yields are pushed down.

Treasury yields, interest rates or risk-free rates - whatever you want to call them - are influenced by the same forces that determine bond yields. Let's take a look at the U.S. 10-year treasury yield (a long-term risk-free rate) as an example. While daily fluctuations in interest rates are driven by multiple forces, like market sentiment and monetary policies enacted by the Fed, they are ultimately determined by two fundamental factors: 1) expected inflation and 2) expected real growth in the economy.

Above is the U.S. 10-year treasury yield laid over a rough measure of an intrinsic interest rate (computed by adding together the actual inflation rate and real growth rate of each year). Notice how the U.S. 10-year treasury yield has moved in sync with the intrinsic interest rate, and that a combination of low growth and low inflation - not the Fed - has been the main reason for a decade of low interest rates. While the Fed does have tremendous influence over rates; ultimately, it is the market that sets them. To further drive this point home, of the $30 trillion in treasuries circulating around the world, only $6 trillion is on the Fed's balance sheet. As a result, it is likely that we will continue to see rising rates if inflation isn't brought under control, regardless of anything announced by the Fed.

The U.S. economy ended 2021 on a mixed note with rapid economic growth accompanied with high inflation, resulting in an intrinsic interest rate running well ahead of the 10-year treasury yield. If history is any guide, that gap will close either with a rise in treasury yields or a steep drop in economic growth and/or inflation.

Inflation and bonds (TLDR): When inflation is higher than expected, bond returns are dragged down by: 1) reduced real return on interest payments and 2) price depreciation as bondholders sell out in search of higher yields.

Inflation and Stocks

To understand how inflation affects stocks, let's establish the drivers of value for a business and how inflation impacts each individual driver.

Revenue Growth: As inflation rises, companies have the option of passing on higher input costs onto their customers by raising prices. Companies with pricing power will be able to weather high inflation environments better than companies without that pricing power, due to their ability to raise prices faster than the rise in inflation without losing business. On the other hand, companies without pricing power may risk losing business as budget conscious customers feel the pinch of inflation and shy away from the higher prices.

Margins: Inflation normally results in companies having higher input costs and results in lower margins if those higher input costs can't be passed onto consumers by raising prices. Therefore, companies with input costs highly sensitive to inflation and revenue growth that can't match will see their margins will drop as inflation rises. Conversely, companies with input costs less affected by inflation and revenue growth that can match or exceed the rising costs, can see their margins remain intact or even increase.

Risk-free rate: As risk-free rates rise, everyone from consumers, to the government, to the individual businesses themselves will face higher costs to borrow money and to service existing debt. Consumers will pull back on discretionary spending as things like mortgages and loans become more expensive, governments may also have to cut spending as the interest expense on their debt rises, and businesses will feel the pain of both lower consumer spending and higher interest expenses on debt. Additionally, companies are traditionally valued by estimating expected future cashflows and discounting it back using a discount rate (an expected return equity investors and lenders demand), which is formed with the risk-free rate as the base. As inflation ticks up higher, the risk-free rate will follow, resulting in higher expected returns demanded by both equity investors and debt lenders. Further, since expected cashflows are effectively worth less the farther out they are in the future, companies earlier in the life-cycle (typically high-growth firms) with little to negative cashflows today promising large expected future cashflows will be significantly more hard hit by rising risk-free rates. Whereas, firms with stable cashflows today and less growth in expected future cashflows may fair better as risk-free rates rise.

Inflation's effect on stocks is arguably somewhat mixed on the individual level, ultimately depending on a company's ability to raise prices enough to deliver high enough revenue growth rates that not only keep margins intact but also negate the adverse effects of higher risk-free rates. However, it's more likely that high inflation would be harmful to stocks as an aggregate, especially if inflation comes in higher than expected.

Inflation and stocks (TLDR): If expected inflation is high but still within expectations, businesses and investors have the opportunity to account for the effects of inflation in their decision making, with investors demanding higher expected returns, and businesses raising prices. However, it's when unexpected inflation catches markets off guard, that we see large fluctuations in stock prices as investors struggle to reassess prices and businesses start seeing their earnings decline.

Inflation and Hedges

Historically, commodities, gold and silver, and real estate have been used not only as a means of diversification but also to protect portfolios from the effects of inflation. Conventional wisdom states that as the demand for goods and services rises, the price of those goods and services will rise as well, as do the prices of the commodities required to produce those goods and services. Gold and silver, while used in many industrial applications, derive their value differently from other commodities. Investors purchase these precious metals because of their long history of being currencies to preserve their purchasing power during times of high inflation. Last, real estate has long been considered to be a great hedge against inflation, since rents and property values typically rise with inflation.

In the table down below, I took the historical annual returns of different assets from 1970 to 2021 and estimated the correlation between each asset and inflation. Correlation can be thought of as how two variables (in this case, two different assets or asset classes) move in relation to each other. Correlations range from -1.0 to 1.0: 1) a perfect positive correlation of 1.0 means that both assets move in lockstep, 2) a perfect negative correlation of -1.0 means that both assets move in opposite direction, and 3) a correlation of 0 means that both assets are uncorrelated. Ideally when looking for inflation hedges, you want to be searching for assets that have a perfect positive correlation with inflation. The numbers you see below each correlation are called t-stats. A t-stat informs you if the correlations are statistically significant, or in other words, that these correlations aren't occurring out of chance. Ideally you want to see a t-stat of either -2 and below or 2 and above.

Over the last five decades, the two asset classes that have moved most closely with inflation are precious metals (gold and silver) and real estate, though a large portion of that correlation can be explained by the 1970s with the U.S. abandoning the Gold Standard. Commodities, contrary to conventional wisdom, have been somewhat of a mixed bag. Copper, wheat, soybean and corn are close to uncorrelated with inflation and less statistically significant, with the exception to crude oil and sugar. Crude oil's strong correlation to inflation can likely be attributed to it being the world's primary source of energy production and the starting point of all consumer products.

Inflation and hedges (TLDR): As inflation rises, the prices of the commodities necessary to produce those goods and services are likely to rise as well. However, while historical data doesn't fully reflect this, crude oil is likely to remain an effective hedge against inflation as long as it remains the world's primary source of energy production. Real estate is considered to be a strong hedge (and the historical data supports it) due to landowners' ability to raise rent prices and property prices' tendency to move up with inflation. Last, while gold and silver's correlation to inflation is largely due to the 1970s, investors may look to these precious metals if they lose confidence in their nation's currency and the financial assets denominated in that currency.

Inflation is Back

Inflation will likely continue to be the main theme influencing markets and the economy. We can also expect that if inflation continues to come in higher than expected for an extended period of time, we will see the unwelcome effects on financial markets and the broader economy. One way to see how much inflation markets are pricing in is to look at a breakeven inflation rate, computed by taking the difference between the nominal treasury yield (for example, the 10-year treasury) and its corresponding TIPS rate (treasury inflation-protected securities). Looking at the chart below, we can see that while the latest inflation number is high, markets are forecasting inflation to ease and come down to around 3% in the next five to ten years.

In other words, your investment decisions will be driven by whether you expect inflation to come in higher or lower than 3% in the near future.

While not the main point of this post, investors will not only have to keep inflation in mind, but pay attention to the effects of rising geopolitical tensions around the world. We are already beginning to see hikes in military spending in many parts of Europe and Asia, as well as a push to revive domestic manufacturing as global supply chains begin to look more like a boon rather than an asset. As nations look to deglobalization, investments towards establishing economic independence and strengthening national security will likely further fuel inflation in the foreseeable future.

Inflation is undoubtedly back and while the reasons for its return are highly debated, what matters now is how bad it will get and how long it will last. And although some economists are expecting inflation to ease in the second half of this year, there is fear that once the inflationary spiral has begun, it may be impossible to contain without heavy economic consequences.